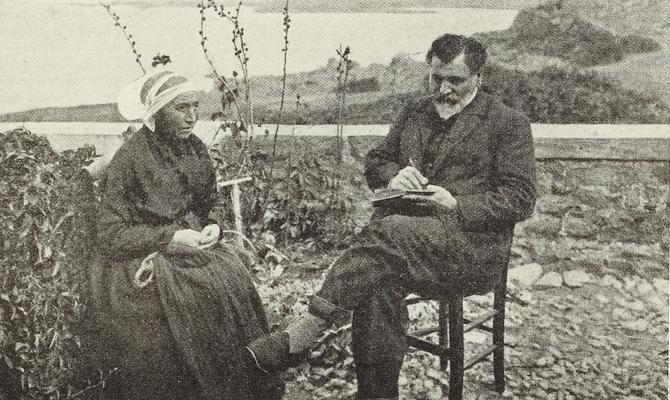

In 1829, in his novel Les Chouans, Honoré de Balzac does not mince his words in his depiction of the Bretons. “An unheard-of ferociousness, a brutal obstinacy, but also a regard for the sanctity of an oath […] unite in keeping the inhabitants of this region more impoverished as to all intellectual knowledge than the Redskins, but also as proud, as crafty, and as enduring as they.” A little later, Gustave Flaubert, who visited Brittany over a three-month period in 1847, played on their reputation in his Dictionary of Received Ideas. “Bretons: all good souls, but stubborn,” he wrote teasingly. Even the celebrated folklorist Anatole Le Braz, author of La Légende de la mort, is brutal when rebuking the Bretons for their legendary obstinacy. He decries, “The Bretons en masse keep the Celtic dream alive, remaining hostile to suggestions from outside, limited to the very narrow beliefs and behaviours of a local identity. They still think today using the heads of their ancient ancestors, without having welcomed a single new brain cell.”

"Fearless and headstrong as a Breton"

So are Bretons as stubborn (pennek in Breton) as all that? The cliché may yet not be scientifically proven, but it certainly follows them around like a bad smell, most notably in the sports sector and particularly where cycling is concerned, a sport Brittany is well-known for. From Lucien Mazan to Bernard Hinault via Louison Bobet, one can list any number of cycling champions from the area. The young Jan Robic, Tour de France 1947 champion, was, in the eyes of the media, a ‘fearless’ cyclist, but above all, ‘stubborn as a Breton’. Later, even comedian Pierre Desproges made light of this character trait. “The obstinacy of the people of Brittany has been scientifically proven. Studies carried out by France's most eminent researchers at the National Centre for Scientific Research demonstrate that in theory a wet Breton performs better under pressure than wet steel. And to put said theory into practice we simply need to boil a Breton. However, so far not a single Breton we’ve contacted in the name of scientific progress has agreed to take part. We can therefore conclude that they are indeed an obstinate bunch, and it’s their fault the reputation of French research lies in tatters.”

Obstinacy of Perseverance?

It may be impossible to prove their obstinacy, but several historical events demonstrate a certain tenacity, or even doggedness. Take the example of the women factory workers at the Dournenez sardine canning plant, who went on strike for 45 days, resulting in a salary increase in 1924. The famous Joséphine Pencalet, the first woman to be elected a town councillor in France and the leader of that movement was perhaps predestined given her name: Penn-kalet means hard head in Breton! It was perhaps also thanks to the tenacity of protestors that the Plogoff nuclear power plant was never built in the 1980s. Not to mention the fourteen-year trial fought by the town councillors of many small coastal towns and villages to receive compensation after the tragic Amoco Cadis oil spill in 1978. Finally, a battle by locals in central Brittany to keep Carhaix hospital open is still ongoing.

Today, some of those concerned have decided to embrace the cliché, even choosing to wear tee-shirts with a phrase designed to stop the teasing for good: “I’m not stubborn, I’m just Breton.”

Translation: Tilly O’Neill