A major Breton presence during the Battle of Hastings

In 1066, Harold was named King of England after the death of Edward the Confessor. However, two other princes also had claims to the throne: Harold the King of Norway and William the Duke of Normandy. The first disembarked on the 18th September 1066 near York and was defeated and killed by Harold. The second, William, berthed in South-East England on the 28th and 29th September. Harold immediately rushed to meet him on a forced march. The two armies fought each other on the 14th October at Hastings. William’s army was composed of three divisions: the Normans at the center, the French and Flemish army on the right and the Bretons on the left. After a long battle, during which the Bretons momentarily took flight, the Duke of Normandy ended up vanquishing his opponent. Harold was killed.

The first wave of migrants

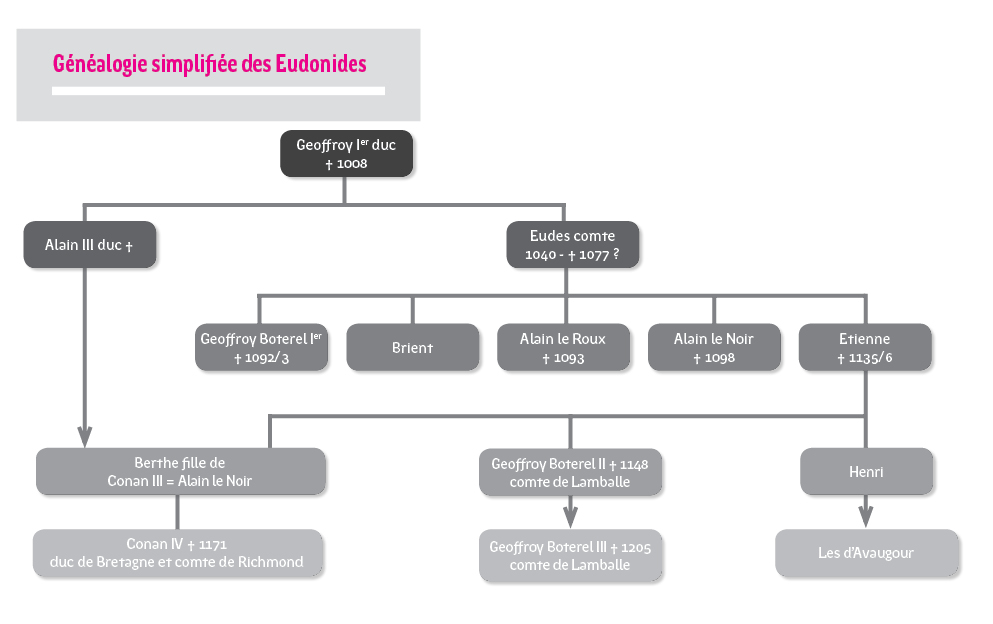

Although there are no known Breton names from the Battle of Hastings, it is likely that Ralph the Staller or Ralph the Englishman as he is otherwise known and Alan the Red and Briant, the sons of Eudes (Alan III Duke of Brittany’s brother), took part in the battle along with all their men. Some amongst them were accorded the lands of the vanquished. It is therefore believed that Briant settled in South West England. We know for certain at least that he rebuffed an attempted invasion there, led by the deceased King Harold’s son in 1069. Nonetheless, William the Conqueror did not initially destruct the Anglo-Saxon aristocracy and preferred to be on good terms.

The period of revolt and the second wave of recruitment

However, from 1067 onwards, the Anglo-Saxons revolted against William who would often overthrow them ruthlessly and replace them with migrants. For instance, Ralph the Englishman’s son, Ralph the Guader, led a failed revolt in 1075 which led to his exile to Brittany. His English territories, consequently unoccupied were then bestowed upon Hugh d’Avranches, the Earl of Chester. The Earl placed vassals there, such as Withenock, son of Caradoc de la Boussac, a nobleman with estates near Dol in Brittany. Similarly, Edwin, the Earl of Mercia’s fall after his revolt in 1070 benefited Alan the Red who consequently attained a firm foothold in what would become the Earldom of Richmond.

New Breton arrivals under Henry I (1100-1135)

Henry I, William the Conqueror’s youngest son, managed to thwart his brothers by becoming King of England in 1100 and Duke of Normandy in 1106. After seizing the throne, he immediately recruited new men in his Breton communities. Subsequently, Alan, the seneschal of Dol’s brother, and William of Aubigné (a region north of Rennes) became part of his administration. After 1116, Henry recruited Bretons associated with the entourage of Etienne, Earl of Brittany and Richmond and brother of Alan the Red (died 1093). These Bretons were originally from the Lamballe commune.

A quantitative estimation of the migration

It follows that 1066 marks the beginning of a Breton migration to England that extended into the 1130’s. It is estimated that the English descendants of the Bretons represented around 5% of the English nobility, which could in turn tally with the 250 knights of Breton origin cited in the 1166 Great Charter. Nevertheless, the Bretons’ ties with the Anglo-Saxons preceded Hastings as is illustrated by Ralph the Englishman, who owned estates in England and Brittany before 1066.

Profile and becoming migrants

The Breton migrants chiefly originated from regions under a Norman or Euden (a prominent Breton family) influence. In other words, the Fougères, Dol-Combourg, Dinan and Lamballe regions. They belonged to small or medium aristocracies or were the legitimate sons or young noblemen of great families, such as the Dinans, the Fougères and the Vitrés. They essentially formed two groups, one was established in the North and the East of England and the other in the South and the West.

The great majority of these migrants settled definitively in England. They married, as early on as the first generation, into the Norman and Anglo-Saxon aristocracy and seemingly, quickly lost their ties with their Breton relations.

The unwavering loyalty to the King of England allowed certain migrants and their descendants to attain a better social position than their relations who had remained in Brittany. Thus, Withenock, son of Caradoc owned the seigneurial manor of Monmouth, whilst the Breton branch of the family’s position did not exceed that of a small village seigneury. It is worth mentioning again the admittedly remarkable promotion of Alan, brother of the Seneschal of Dol: he is the ancestor of the Stuarts who reigned in Scotland and England.